A socially-distanced chemistry lab class led by Professor of Chemistry Blake Gillespie

Faculty have a few tricks up their sleeves to make online instruction in the time of COVID-19 fun, formative and fair.

by Marya BarlowWhen classes shifted online last spring, CSUCI Performing Arts faculty members Heather Castillo and MiRi Park faced a challenge unique even among educators: How do you teach students to dance when all they’ve got to work with is four square feet of space and a smartphone?

Fortunately, Castillo and Park had faced that problem before. Through wildfires, campus closures, and other disruptions, they’ve become adept at keeping CSUCI students dancing online. In the COVID-19 pandemic, they saw an opportunity not only to improve their skills, but also to share knowledge with a global community of educators and dancers trying to navigate virtual learning.

In a published guide, online workshops and webinars, the duo imparts their trials, tribulations and tips. They launched CORontine Corps, an online space for dancers from around the world to share and archive performances and virtual education best practices. They also helped start the CSU Dance Collective, a collaboration to foster virtual creative exchange between all CSU dance programs.

Their resources were so popular they received thousands of views on the web, won endorsement from the Dance Studies Association, and were adopted by universities around the world. In August, Castillo and Park earned recognition from the CSU Chancellor, who honored them with a 2020 Faculty Innovation and Leadership Award, recognizing extraordinary leadership that advances student success.

“It was an unintended special honor,” said Castillo. “I was well supported at CSUCI to teach and mentor others as a Teaching and Learning Innovation faculty fellow. MiRi and I had a little bit of a head start in online instruction and wanted to use it to help the entire dance community.”

Castillo, an assistant professor and veteran professional dancer and choreographer, teaches students from a makeshift studio (formerly her children’s playroom) in her Thousand Oaks home. She intentionally made the space small, so her movements are restricted to match those of students joining class from cramped bedrooms and hallways. Two cameras and a large wall mirror capture her instruction from different angles, while she coaches students in real time on gallery view from her computer.

Park is a CSUCI lecturer, professional dancer, choreographer, producer and scholar. Each week she introduces new movement to students in pre-recorded videos and then meets with the class for synchronous practice and feedback. She also incorporates a strategy developed by Castillo to connect with students in smaller group cohorts — ensuring they get individualized attention and maintain ties to each other.

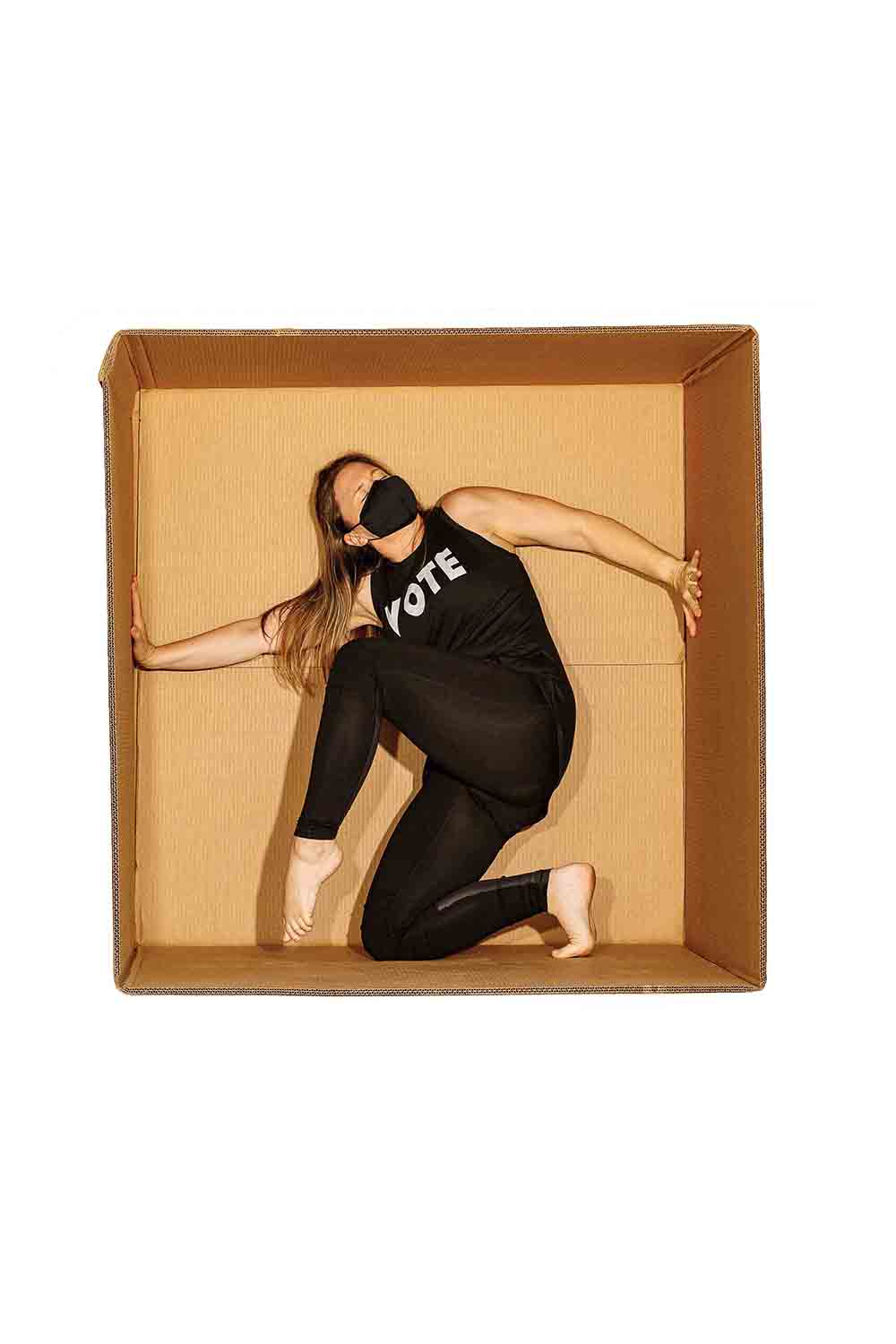

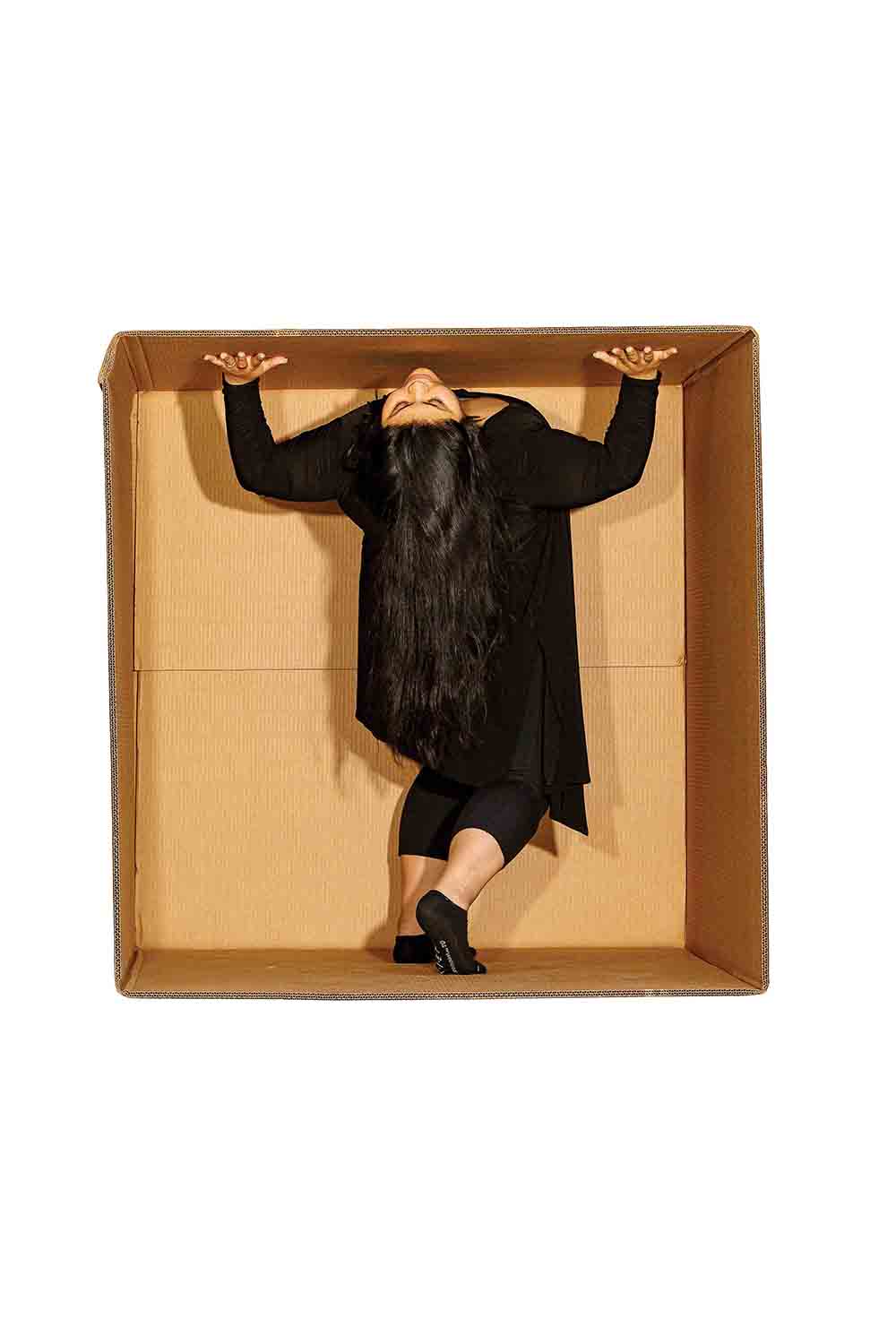

Dancers in Heather Castillo's class work on themes of confinement

Dancers in Heather Castillo's class work on themes of confinement

While online instruction is not ideal — Castillo says it’s more than three times the work of an in-person class — there are silver linings. Students who never danced before are flourishing. Experienced students say that leaving the studio, with its big wall mirrors and capacity for comparison with classmates, gives them more freedom to forge comfortable identities as dancers.

For her Dance Ensemble class, Castillo provided all 12 students with a four-foot-square cardboard box for a project she’s calling, “Boxed In.” Each week, students use the boxes as a stage or canvas to explore their sense of containment during COVID-19 through movement, art and journaling. Their recorded video performances will be presented at the end of the year in a CSU Dance Collective virtual concert.

“I’m surprised how much they are learning,” she said. “It takes more time to do it well and do it safely, but is it important that we keep doing it in this moment? Heck, yeah.”

Castillo and Park have spread their work to build online community beyond the field of dance. Answering the call to action in the Black Lives Matter movement, Park launched an educational activism project called the ReadIn series, with Castillo as co-producer. They enlisted noted Black actors, broadway stars and scholars to read aloud in an online read-a-thon of “Black Reconstruction in America,” a resonant historical text by civil rights leader, educator, writer and scholar W.E.B. Du Bois. The series has drawn widespread interest and acclaim.

“I feel fortunate that we can still connect and be politically, socially and physically active in this medium,” Park said. “I’m proud to say that I teach at a place that values the online learning space with equity in mind.”

Experimenting with Virtual Learning

For CSUCI Chemistry professor Blake Gillespie, life is one big experiment. So, naturally, when classes moved online due to COVID-19, he embraced the pandemic as an experiment in virtual learning.

Gillespie converted his garage and backyard in Santa Barbara into makeshift laboratories to perform experiments for students such as using ethanol to make gunpowder explode (with the unequivocal warning: “DO NOT TRY THIS AT HOME!”). Still, something was missing.

“Blowing stuff up in the backyard, really, I got zero positive feedback about that from students, which was deeply discouraging,” he said. “But it cemented my conviction that students learn best when they do something, create something.”

By fall, Gillespie had revamped online classes to ensure all students could “engage with their learning to be creators, not consumers.”

His Molecular Structure Determination course blends in-person and online learning so students can actively participate from the lab or home. On campus — socially distanced and wearing full PPE — students learn about structure in biomolecules by growing crystals of proteins in the lab.

Students who are unable to come to campus can join online, in real time or asynchronously via video feed of the lab’s microscopes. They help score the experiments that in-person students began and identify the best conditions for obtaining crystals.

After growing the crystals, the students mount and ship them in liquid nitrogen to Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource at the Stanford University/U.S. Department of Energy SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory. From 350 miles away, the students operate a remote-controlled robot to perform research and data collection. The virtual machine environment was set up with the help of CSUCI’s Information Technology Services so all students can use the same software tools remotely, regardless of variations, disparities or inequalities in technology access.

“The real story is that we're able to do some scientific heavy-lifting using remote-learning technologies,” Gillespie said. “In the grown-up world of biomolecular structure determination, folks often don't collect data manually, in person. The best facilities are remote-access, shared-use laboratories. So, our students are actually having quite a 'real-world' experience, partly because of the pandemic.”

Gillespie also enthuses about some of the ways virtual learning has enriched an interdisciplinary course called “Science/Fiction” that he co-teaches with Assistant Professor of English Raquel Baker.

“Raquel and I tag team on managing the discussion, breakout rooms, and group chat,” he said. “We've had some really powerful student insights about our readings, and I feel like I've grown as a result of them. Because it's all discussion/creation all the time, students step up, come ready to work, and even support us by drawing our attention to pieces we might miss, like someone raising their hand or a comment in chat. In this class, we’ve seen a level of excitement and buy-in that all professors dream of, regardless of delivery modality.”

Return to the Table of Contents

© Fall 2020 / Volume 25 / Number 2 / Biannual