By Kim Lamb Gregory

Armed with a bag and a snake hook, CSUCI Assistant Professor of Biology Rudolf von May, Ph.D., and another scientist followed the light from their headlamps as they walked slowly through the Amazon rainforest.

“We would scan every possible tree trunk and plant,” von May said. “When we would find something moving or the eyes would shine, we would catch it, take a quick look, and put it in a bag.”

Then, the scientists would take the specimens back to camp to study them.

Von May was cataloguing the species of amphibians and reptiles in the Peruvian Amazon, part of an international multi-year, multi-disciplinary research project aimed at providing evidence for protecting more areas of the Amazon.

“Most of the areas rich in biodiversity are part of the ancestral territories of Amazonian indigenous people,” von May said. “The formal protection of these areas helps conserve the biodiversity and the traditional ways of life of local communities.”

From 2000 to 2016, scientists from around the world conducted what’s known as a “rapid inventory” — a fast survey of remote areas — in 14 different regions covering more than nine million hectares (one hectare contains about 2.5 acres). This process involved a team of biologists who studied plant and animal species, while a team of social scientists researched indigenous communities.

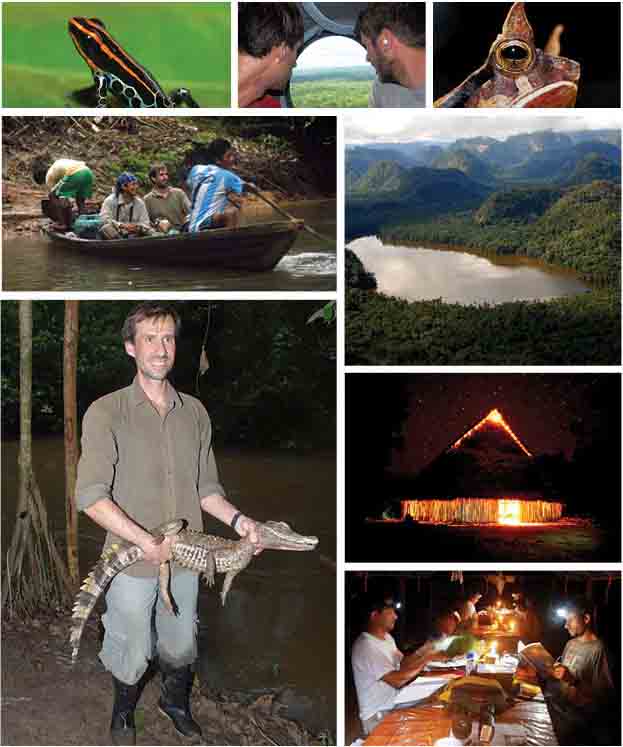

CSUCI Biology professor Rudolf von May adventuring by plane and boat through the Amazon

and interacting with the wildlife and native inhabitants.

The rapid inventories involved hundreds of scientists and indigenous partners from different ethnic groups. Von May himself hails from Peru, which is home to about 13% of the Amazon rainforest. Von May conducted field study in 2009 and 2010 and then continued to collaborate with his colleagues.

The research team concentrated on Loreto, the largest state in Peru. Loreto has few roads, so researchers traveled by boat and helicopter, then camped for three weeks for each inventory.

The project was funded by a number of organizations and donors, and was coordinated through the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, Illinois.

Field Museum ecologist Nigel Pitman, Ph.D., who was lead scientist on the project, wrote a blog for the New York Times about the Amazon experience, including one piece about what it was like to follow von May and fellow herpetologist Jonh Jairo Mueses-Cisneros of Colombia one night after the moon rose over the trees.

“As they work, the beams of their headlamps go sweeping restlessly through the forest,” Pitman wrote. “They go on working through the leaf litter with their snake hooks, turning over rotting logs, searching around the bases of buttressed trees, and wading off the trail now and then to investigate some intriguing eye shine.”

“Peru is a developing country and faces many challenges,” von May said. “While the government is interested in attracting investors, it must remain committed to protecting the Amazon and the rights of indigenous people.”

Pitman, von May, and their colleagues recently published a report in “Science Advances,” the open access journal of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Since the team presented the research to local policymakers nine of the 14 landscapes — about 5.7 million hectares (an area larger than the Central Valley of California) — have been designated as protected areas.

Return to the Table of Contents

© Fall 2021 / Volume 26 / Number 2 / Biannual