Professor, student researchers find microplastics in harbor moon jellies

By Kim Lamb Gregory

Assistant Professor of Environmental Science & Resource Management (ESRM) Clare Steele knelt on a wooden pier at the Channel Islands Harbor and dipped her net into the water.

“Half of being a marine biologist is not falling in,” Steele joked.

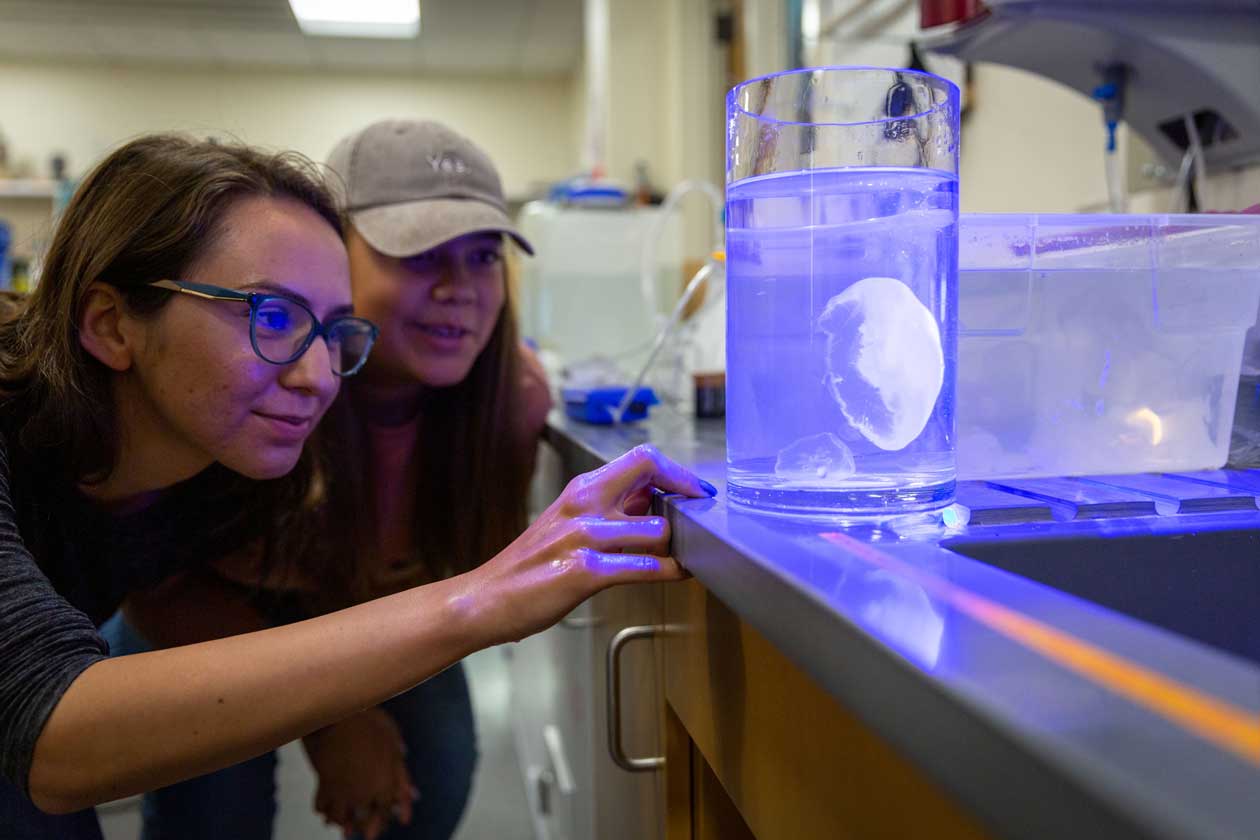

She slid her net under a translucent moon jelly, scooped it up and deposited it into a plastic cooler. When she had collected several, she snapped down the top of the cooler and transported the jellies to a CSUCI lab where Steele and her ESRM students would examine the sea creatures for microplastics.

Steele and her students have been conducting studies into microplastics in the ocean for about four years now, so when thousands of the gelatinous invertebrates swept into the Harbor in early April, Steele and her students decided to test them.

“We found microplastics in all 10 of the jellies we processed,” Steele said. “It’s a representative sample of an organism that has a different feeding mechanism than the ones we’ve looked at so far.” In other words, moon jellies are largely at the mercy of the ocean currents, so they feed on whatever gets caught in the mucus lining of their bell-shaped bodies.

“We found microplastics in all 10 of the jellies we processed,” Steele said. “It’s a representative sample of an organism that has a different feeding mechanism than the ones we’ve looked at so far.” In other words, moon jellies are largely at the mercy of the ocean currents, so they feed on whatever gets caught in the mucus lining of their bell-shaped bodies.

Earlier studies indicating microplastics in the sand of all 50 beaches tested up and down the California coast told Steele and her research team that microplastics are ubiquitous in coastal waters, but the presence of microplastics in moon jellies, which move by pulsing their bells up and down through columns of water, are even more of a concern.

“It should concern people that plastics of all sizes are in the oceans and waterways,” Steele said.

“Another thing that concerns me is that as plastics break up into smaller and smaller pieces, they become more difficult to detect and difficult to remove.”

If we can remove plastics before they get into the ocean, we have a chance to keep them out of the food chain.

Clare Steele

Plastics in the ocean and estuaries mean plastics are getting into the food chain, and therefore, into us, she said. “One of the concerns we have with microplastics is that their surfaces have an affinity for attracting environmental chemicals, maybe DDT (a synthetic organic compound used as an insecticide) or some sort of organic pesticides,” she said.

The California State Senate invited Steele to testify about microplastics before a joint hearing of the Senate Committee on Environmental Quality and Committee on Natural Resources and Water on March 20. The hearing preceded the reading of Senate Bill 54, which would, if passed, phase out single-use plastics by 2030.

The California State Senate invited Steele to testify about microplastics before a joint hearing of the Senate Committee on Environmental Quality and Committee on Natural Resources and Water on March 20. The hearing preceded the reading of Senate Bill 54, which would, if passed, phase out single-use plastics by 2030.

Whatever lawmakers decide, Steele and her student researchers intend to use scientific methods to keep vigil on California’s coastal waterways. “If we can remove plastics before they get into the ocean, we have a chance to keep them out of the food chain,” she said.

Return to the Table of Contents

© Spring 2019 / Volume 23 /Number 01 / Bi-annual