The Process Is as Important as the Agenda

When called upon to make a decision as a group, we often default to methodologies we are most familiar with (e.g., voting or unanimous consent), even in virtual environments like Zoom or Teams. In many cases, these methods work well. However, even when the methodology employed suits the goals of the leader and group, there are tradeoffs made in settling upon a particular method. Similarly, external constraints may limit the effectiveness of certain methodologies. Instead of defaulting to the familiar, it is best to make the tradeoffs knowingly and in advance of the decision point.

In general, three considerations should guide your preparations:

- Start from implementation

- Find your tradeoffs (see chart below):

- Make it “sign here”-able

Implementation-mindedness

The late Dr. Steven R. Covey said, "begin with the end in mind." He was talking about beginning a work with a sense of vision as to what will be achieved by the work. The same principle applies regarding a decision that will need to be made in a virtual setting. When it comes to framing your virtual decision-making process, you need to have a vision of the kinds of next steps that will need to happen after the decision is made. Even when potential options seem to be polar opposites, there are common elements to all options as well as resources. Be clear where those commonalities lie.

For example, consider who will be involved in implementing any decision, regardless of what the decision may be. Consider what primary resources will be needed in implementing any decision, regardless of what that decision may be. And consider which stakeholders will be affected, regardless of what the ultimate decision may be. By having an idea about these core limiting factors at the outset, you can develop a process with the right people and resources in mind and know where the fundamental limitations lie.

Tradeoffs

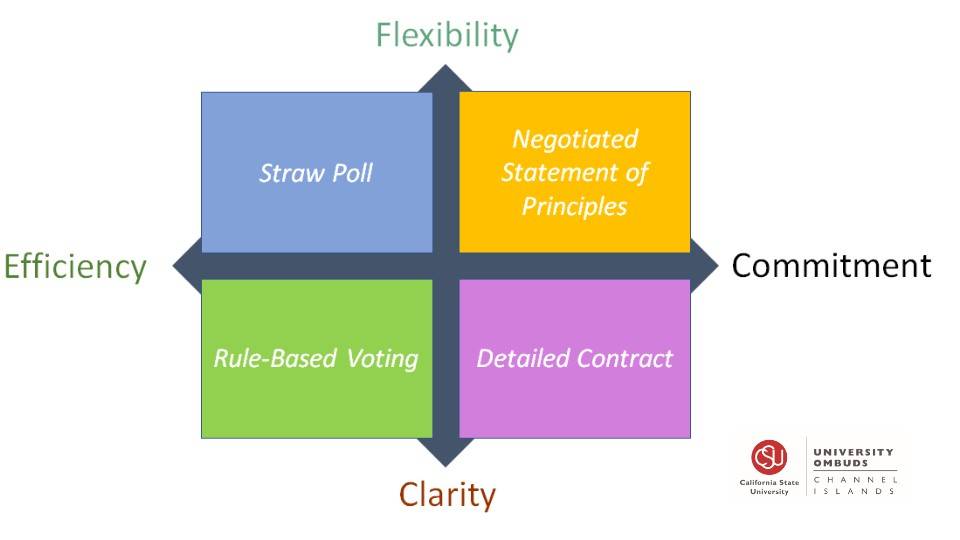

There is an old saying in business: "Fast, cheap or good-- you can have any two, but not all three." In a similar fashion, there will always be tradeoffs in choosing a decision-making methodology. The chart below provides some insight into how to consider sometimes competing interests in varying methodologies. The axes considered are "efficiency vs. commitment" and "clarity vs. flexibility." There could be other axes in your situation, but these are good ones to start from.

The methodologies shown in each quadrant (clockwise from top left, "straw poll," "negotiated statement of principles," "detailed contract" and "rule-based voting") are representative only, not indications of the only methodologies available in each category.

A "Sign-here-able" decision

When savvy trial lawyers want to win a motion during litigation, they don't leave it up to the judge to craft the order on their own. They make it as easy as possible for the judge to simply "go along" by doing her work for her, down to the signature block. Although party-drafted orders are rarely implemented as written, they carry great persuasive weight because of our human desire to conserve energy and avoid unknowns.

The same holds true in structuring a decision-making process online. Because of the uncertainties of implementation when parties are dispersed and limited in their communications, participants and stakeholders will need to feel even more confident about the boundaries of a decision to be made. This frees the participants to move forward with confidence and creativity at the outset.

A simple example of establishing decision boundaries would be for a meeting organizer to share a written template with universal "implementation-minded" factors outlined with open-ended action phrases to address the factors. For example, a shared document might say, "We will ___________ with contracting." In a face-to-face meeting environment, such simple cues might seem awkward and stiff. But in a virtual realm where many interpersonal cues are lost (facial expressions, body language, ability to signal focus and interest by physical movement), organizers need to prime participants' feelings of control by suggesting certain limiting factors will be addressed or will not be addressed in visible ways. Using simple prompts in a virtual environment helps compensate for missing (often subconscious) signals people look for in face-to-face meetings.

Conclusion

Good group decision-making requires good data, committed participants and a good process. The virtual environment provides new opportunities for creativity in making decisions. But it also includes some pitfalls. With trained resources and experiences in conflict management systems design, the Ombuds Office can help your organization mindfully harness the opportunities while minimizing the weaknesses.